Many battery issues stem from temperature extremes, so you must manage heat to prevent thermal runaway and overheating. Implement active cooling, passive conduction paths, and precise sensors to maintain optimal ranges, balance cells, and enable fast fault detection. These measures reduce risk and deliver extended cycle life and improved performance for your packs.

Types of Thermal Management Strategies

| Passive conduction / air cooling | Cell spacing, conductive plates, aluminum housings; typical use in consumer packs and low-power EVs for simplicity. |

| Heat pipes / graphite spreaders | High effective thermal conductivity (graphite ~200-400 W/m·K); used at module level to spread transient heat bursts. |

| Active forced-air cooling | Fans and ducts, removes a few hundred watts in pack-scale systems; low cost but limited when cells are tightly packed. |

| Active liquid cooling | Coolant loops with pumps and heat exchangers, maintains pack temperature within ~20-40°C under heavy duty cycles; common in modern EVs. |

| Phase change materials (PCM) | Latent heat absorption (paraffin ~150-250 kJ/kg); reduces short-term peak temperatures but adds mass and requires thermal augmentation. |

- Passive cooling

- Heat spreaders / heat pipes

- Forced-air active cooling

- Liquid active cooling

- Phase change materials (PCM)

Passive Cooling Techniques

You rely on passive conduction and natural convection when space, weight, or cost constrain active systems; thermal paths are optimized with materials like aluminum (>200 W/m·K) or copper (~385 W/m·K) for casings and busbars, while graphite spreaders provide effective in-plane conduction for pouch cells.

In practice, you can achieve acceptable performance for moderate duty cycles by combining tight mechanical contact, high-conductivity TIMs, and deliberate cell spacing; for example, a well-designed passive pack for an e-bike or low-power stationary storage can limit peak cell-to-air ΔT to <20°C under 1C discharge, but be aware that thermal runaway initiation still occurs above ~150-200°C and passive designs offer limited protection against rapid, high-energy events.

Active Cooling Techniques

You implement forced-air systems when transient heat must be moved quickly without liquid complexity; small axial fans and optimized ducting typically handle a few hundred watts for module-level cooling, and are common in pack prototypes and low-cost applications.

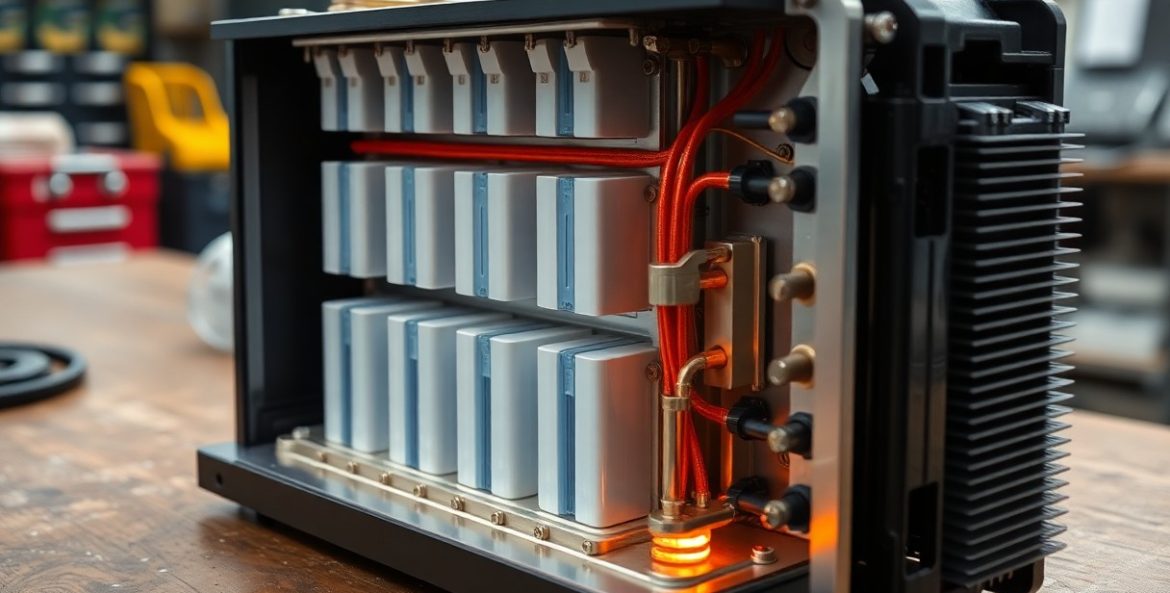

When duty cycles or power density exceed what air can handle, you switch to liquid cooling – cold plates, direct cell jackets, or interleaved channels – which can keep a large pack within the target window (commonly 20-40°C) during rapid charge and sustained discharge; many EV manufacturers use liquid loops to control cell temperatures during high-power events.

Design trade-offs you must quantify include pump power (typically in the tens to low hundreds of watts for automotive packs), leak mitigation, and control integration with the BMS to modulate flow and valve states for uniform cell temperatures.

Thou should weigh mass, cost, reliability, and safety when choosing between forced-air and liquid systems.

Phase Change Materials

You employ PCM to absorb short-duration, high-rate heat pulses without active hardware; materials like paraffin provide latent heat ~150-250 kJ/kg and are often encapsulated in metal or polymer shells to prevent leakage and to increase safety.

Performance improves when PCMs are combined with conductive enhancements – graphite foams, metal fins, or embedded copper strips – because raw paraffin has low thermal conductivity (~0.2 W/m·K); studies show PCM-augmented modules can reduce peak cell temperatures by ~10-15°C during high-current pulses (e.g., 3-5C bursts) compared with non-PCM packs.

You must also consider long-term behavior: melting/freezing cycles, potential flammability of some organic PCMs, and the additional mass and volume that can impact energy density and packaging.

Factors Influencing Thermal Management in Lithium Ion Batteries

Multiple parameters interact to define how you manage heat at cell, module, and pack levels. Key drivers include chemistry, cell form factor, ambient environment, and your expected charge/discharge C-rate – each alters heat generation, thermal conductivity paths, and safety margins. Practical examples: a pack using 21700 cells at sustained 2C discharge will generate roughly four times the resistive heating of the same pack at 1C because heat scales with I²R; likewise, storing cells at high SOC increases the energy available during abuse events and raises propagation risk.

- Battery Chemistry

- Operating Conditions

- Design Considerations

- Cell Form Factor

- State of Charge (SOC)

- Thermal Runaway

In real systems you must quantify these factors: measure internal resistance drift across cycles, map hot spots with thermal cameras during standardized 1C/2C tests, and model worst-case thermal runaway scenarios for the chosen chemistry and SOC. Perceiving

Battery Chemistry

Your choice of cathode and electrolyte chemistry sets the baseline for both heat generation and abuse behavior. For example, high-energy chemistries such as NMC or NCA typically offer higher specific energy (often in the range of ≈200-260 Wh/kg) but present earlier onset of exothermic decomposition under thermal abuse; many high-energy cells exhibit SEI and electrolyte breakdown beginning above ~90-120°C with escalating oxygen release from layered cathodes at higher temperatures. By contrast, LFP chemistries trade lower nominal energy density (commonly ≈110-180 Wh/kg) for improved thermal stability and reduced oxygen evolution, which lowers the likelihood and severity of thermal runaway propagation.

Because you will face different failure modes depending on chemistry, adjust your thermal strategy accordingly: high-energy packs often require more aggressive active cooling and faster cell balancing to limit high-SOC exposure, whereas LFP packs can sometimes prioritize simpler conduction paths and cost-effective passive measures while still benefiting from targeted cooling during fast charging.

Operating Conditions

How you operate the battery-particularly the C-rate, ambient temperature, and duty cycle-directly controls instantaneous heat generation. Heating power follows I²R, so doubling discharge current multiplies resistive heating by four; in practice, sustained fast charging at 2-3C can raise cell temperatures by tens of degrees within minutes unless you provide adequate cooling or reduce charge power as temperature climbs. You should also model transient events: high-power accelerations, regenerative braking spikes, and frequent short pulses create different thermal gradients than steady-state driving.

Ambient extremes change both performance and cooling requirements: sub-zero operation increases internal resistance and can shift hotspot locations, while hot climates reduce thermal headroom for fast charge and increase the risk of parasitic self-heating during storage. Managing SOC windows matters too-operating regularly above ~80-90% amplifies the energy available during an abuse event and accelerates side reactions that raise internal heat generation.

When validating your design, run combined tests that mirror real use: repeat 2C charge/discharge cycles at 40°C ambient, perform soak tests at high SOC for 24-72 hours, and instrument cells with surface and core thermocouples to capture worst-case gradients and inform your BMS thresholds.

Design Considerations

Cell form factor and mechanical layout create the thermal pathways you can exploit: cylindrical cells conduct heat through the can and to end caps, which suits designs with coolant plates or compressed stacks; pouch cells rely on tab conduction and external TIMs or graphite sheets for lateral dissipation; prismatic cells fall between the two. Spacing, mounting torque on busbars, and thermal interface materials all alter contact resistance-small changes produce measurable shifts in hot-spot temperature under high-rate cycling.

Materials and subsystem choices also affect your options: integrating cold plates with liquid loops gives high heat-removal capacity for EV packs, while phase change materials (PCM) or graphite-enhanced thermal spreaders can blunt short transients in heavier consumer or stationary systems. Sensor placement and control logic are part of design too-placing temperature sensors only at module corners can miss central hotspots in large prismatic assemblies, so you must map likely maximums and locate sensors accordingly.

Implement design-for-safety measures such as module firewalls, venting paths, and cell-level fusing while validating with abuse tests (e.g., nail penetration, external heating to defined rates) so you can quantify propagation times and required intervention cooling capacity. Perceiving the combined influence of chemistry, operating profile, and mechanical layout lets you set effective thermal control targets and BMS interventions.

Step-by-Step Guide for Implementing Thermal Management Solutions

| Step | Key Actions |

|---|---|

| Assessing Thermal Needs | Measure operating profiles, map hotspots with IR/thermocouples, run electro-thermal simulations (CFD, COMSOL), define max cell delta-T and allowable peak temperatures |

| Selecting Appropriate Materials | Choose TIMs, PCMs, metals (Al, Cu) and coolants based on conductivity, specific heat, electrical insulation and flammability; compare thermal conductivity and latent heat metrics |

| Integrating Solutions into Battery Design | Design cell spacing, cooling channels or heat spreaders, sensor placement and busbar layout; prototype and validate under charge/discharge cycles and abuse tests |

Assessing Thermal Needs

You should start by quantifying heat generation across your expected duty cycle: steady-state losses at 0.1-0.5 W per cell at low C-rates can spike to >1 W per cell during high C events, and module-level dissipation can reach tens to hundreds of watts. Use a combination of instrumentation (thermocouples between cells, IR thermography for surface mapping, coolant inlet/outlet sensors) and physics-based models (electrochemical-thermal coupling in COMSOL or ANSYS) to capture transient behavior and worst-case abuse scenarios.

After collecting data, establish performance targets such as maximum pack temperature (commonly 45-55°C for many Li-ion chemistries), maximum cell-to-cell temperature gradient (<5°C for high-power packs), and the allowable time at elevated temperature before protective actions. Prioritize locating and mitigating hotspots because a single hotspot that reaches ~150°C can initiate thermal runaway, while a uniform pack temperature rise is generally less damaging to cycle life.

Selecting Appropriate Materials

Your material choices should balance thermal performance, electrical safety, mass, cost and manufacturability. Metals like aluminum (≈205 W/m·K) and copper (≈385 W/m·K) are excellent heat spreaders for busbars and plates; TIMs with conductivities in the 1-10 W/m·K range reduce interfacial resistance when applied with thin bondlines (<0.5 mm). For transient events consider phase change materials (paraffin-type PCMs with latent heats around 150-250 kJ/kg) to absorb spikes, and for dielectric safety evaluate non-conductive coolants such as 3M Novec or engineered hydrofluoroethers when direct liquid immersion is considered.

Evaluate each candidate against chemical compatibility with cell casings and electrolyte, flammability, and long-term stability: for example, water-glycol offers high specific heat and low cost but is electrically conductive and requires robust sealing, while dielectric fluids lower short-circuit risk but typically have lower specific heat and higher cost. Use laboratory thermal conductivity tests (ASTM D5470-style setups) and small-scale cycling with the material in-situ to validate performance before committing to pack-level designs.

In practice, hybrid approaches often work best: combine a thin high-conductivity TIM layer to minimize contact resistance, aluminum cold plates to provide uniform conduction paths, and localized PCM blocks to blunt short-duration peaks. That combination can lower peak cell temperatures by 5-15°C in typical power profiles while adding modest mass.

Integrating Solutions into Battery Design

When embedding thermal elements into the pack, integrate thermal pathways early in the mechanical layout: orient cells to optimize contact with cold plates or heat spreaders, route busbars to avoid insulating thermal bridges, and allocate channels for coolant flow that minimize pressure drop while ensuring uniform flow distribution. Run CFD on the pack geometry to size channel cross-sections and predict local heat transfer coefficients; many EV packs target a maximum temperature rise of <10°C across the module under a standardized drive cycle.

Design for serviceability and safety: include redundant temperature sensors (cell surface and coolant), pressure/flow monitoring for liquid systems, and drain/containment measures for potential leaks. Validate the integrated system through combined thermal, vibration and electrical abuse tests per standards such as IEC 62133 and UN38.3; during validation, focus on scenarios that produce sustained power (e.g., repeated 2C discharge) and short transients (e.g., fast charging pulses) to confirm the system meets both performance and safety targets.

Finally, iterate using prototype testing: instrument a module with dense thermocouple arrays and run repeated mission-profile cycles, then refine materials, channel routing and control strategies (pump speed, valve actuation, or fan curves). That iterative approach typically reduces cell-to-cell variance and uncovers assembly issues that models alone will not reveal.

Tips for Effective Thermal Management

You should set operational targets such as keeping cell temperatures between 15-35°C, limiting pack temperature gradients to <5°C, and tracking short-term peaks above 40°C because elevated cell temperature accelerates capacity fade (chemical reaction rates roughly double per 10°C). Implement both hardware controls and procedural checks: combine passive design (spacing, TIMs, conductive plates) with active systems and a robust BMS that logs events at ≥1 Hz for transient analysis.

- thermal management

- BMS

- cooling channels

- phase change materials

- airflow design

The best programs tie sensor data, periodic inspection, and maintenance windows into one actionable dashboard and enforce thresholds for immediate mitigation.

Regular Monitoring and Maintenance

You must monitor temperature sensors, current shunts, and cell voltages continuously and review aggregated logs weekly to spot trends (for example: repeated 65-80% SOC fast-charge events that coincide with 5-10°C temperature rises). Calibrate or replace temperature sensors annually and perform capacity/impedance checks every 6-12 months to detect early cell imbalance or rising internal resistance; these tests help predict end-of-life sooner than voltage inspection alone. Highlight hot spots in thermal maps and treat them as high-priority faults because a single local thermal excursion can trigger thermal runaway.

You should schedule preventive maintenance items: inspect and retorque busbars quarterly, replace air filters monthly in forced-air systems, and reapply or replace thermal interface materials (TIMs) every 3-5 years depending on thermal cycling history. When you detect a repeat over-temperature event, isolate the module, run an impedance spectrum or cell-level capacity test, and log corrective actions in the BMS for trend analysis.

Utilizing Advanced Technologies

You can reduce peak temperatures and improve uniformity by adopting targeted solutions such as multi-loop liquid cooling, embedded heat pipes, and phase change materials (PCM) for transient buffering; combining these with an AI-enabled BMS gives predictive control and can preemptively reduce power draw to keep temps within target. In field pilots, combining PCM with active liquid cooling reduced short-duration peak temps by about 5-8°C, translating to measurable improvements in cycle life.

You should balance benefits against penalties: active cooling typically adds mass and consumes parasitic power (commonly around 1-3% of pack energy over a drive cycle) and increases system complexity and maintenance requirements. Use sensor fusion (cell thermistors + surface IR + inlet/outlet coolant data) and run model-in-the-loop tests to validate that an advanced system actually reduces maximum cell temperature and variance under worst-case duty cycles.

- Liquid cooling: high steady-state heat removal, good for continuous high-power use.

- Heat pipes/vapor chambers: passive redistribution of local heat with no parasitic power.

- Phase change materials: absorb transients, reduce short-term peaks but add weight.

- Thermoelectric coolers (TEC): precise local cooling, low COP, use selectively.

- AI/predictive BMS: reduces peaks by adjusting power/thermal controls preemptively.

Advanced Technology Comparison

| Liquid cooling | High continuous capacity; good for EVs and high-power systems; requires pumps and plumbing. |

| Heat pipes / vapor chambers | Passive redistribution of hotspots; low maintenance; limited absolute heat removal. |

| Phase change materials (PCM) | Buffers peak transients 1-10 minutes; adds mass and must be paired with active cooling for steady-state heat. |

| Thermoelectric coolers (TEC) | Local spot cooling for sensitive modules; low efficiency-best for small-scale or emergency use. |

| AI-enabled BMS | Predictive control cuts peak temperature and smoothing duty cycles by adjusting charge/discharge schedules. |

Combining complementary technologies-such as PCM for transients plus liquid cooling for sustained load-often yields the best trade-off between weight, energy penalty, and temperature control.

Educating Users on Best Practices

You should instruct end users and operators to avoid frequent high-SOC fast charging in hot ambient conditions (for example, avoid >0.5C fast charges when ambient >35°C) and to store packs at 30-50% SOC for long-term idle storage; these steps materially slow calendar aging. Provide concrete limits in manuals: recommended storage temperature 15-25°C, long-term SOC 30-50%, and maximum recommended continuous pack temperature of 40°C.

You must train operators to act on thermal alarms-reduce power, enable auxiliary cooling, or isolate modules-and to perform simple visual checks such as inspecting cooling fans and coolant levels weekly. Include clear labeling at service points and in UI prompts that explain why high SOC + high temperature is dangerous and what immediate actions to take when an over-temperature event is detected.

- Charge strategy guidance: stagger charging and avoid back-to-back fast-charge sessions in hot conditions.

- Storage rules: recommend SOC and temperature ranges for varying storage durations.

- Operational checklists: pre-use thermal inspection and post-high-load cooldown procedures.

- Training cadence: initial training + refresher every 6-12 months for technicians and operators.

User Best Practices

| Action | Why it matters |

| Store at 30-50% SOC | Reduces stress reactions that accelerate capacity loss during storage. |

| Avoid charging >0.5C above 35°C | Limits heat generation and the risk of sustained high pack temperatures. |

| Inspect cooling components monthly | Ensures airflow and coolant circuits are functioning before thermal issues arise. |

You should implement measurable KPIs-such as target maximum pack temperature, mean temperature spread, and reduction in thermal events per 1,000 cycles-and train staff to log every thermal incident so you can iterate on SOPs and engineering fixes.

Pros and Cons of Different Thermal Management Approaches

When weighing trade-offs across design, you need clear comparisons to choose the right approach for your application. The table below breaks down the major strategies so you can quickly scan which method matches your performance, cost, weight and safety priorities.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Passive conduction / air cooling: Low cost, simple implementation, no moving parts, minimal maintenance; effective for low-to-moderate power densities and stationary applications. | Limited heat removal capacity; typical cell-to-cell gradients can reach 5-10°C under moderate loads, reducing cycle life and risking hot spots under peak demand. |

| Liquid (cold-plate) cooling: High heat transfer rates, can maintain pack uniformity to within ±2-3°C, widely used in modern EVs for high-power duty cycles. | Higher complexity, plumbing and pumps add weight and cost (often hundreds to a few thousand USD per pack), potential leak paths and service needs. |

| Phase change materials (PCM): Passive thermal buffering during short high-power events, provides latent heat absorption without active controls. | Adds mass and packaging volume, limited recharge rate for sustained heat loads, potential long-term material degradation and containment challenges. |

| Heat pipes / vapor chambers: Very high effective thermal conductivity for local hot-spot smoothing, passive and reliable for spreading heat. | Integration complexity and cost increase for large-format packs; performance depends on orientation in some designs. |

| Active air cooling (fans): Lower cost active option, easy to retrofit, effective for moderate heat loads and improving convective heat transfer. | Fans consume power, introduce noise and moving-part reliability issues; limited performance compared with liquid cooling at high loads. |

| Thermoelectric (Peltier) cooling: Precise local temperature control possible, useful for small packs or cell-level thermal balancing. | Very low energy efficiency (COP <<1 in many cases), high electrical draw makes it impractical for large systems except niche uses. |

| Immersion cooling: Exceptional heat removal and uniformity, allows very high C-rate operation and compact packaging. | Special dielectric fluids required, complicates maintenance and recycling; higher upfront cost and potential compatibility issues with cell materials. |

| Integrated structural cooling: Dual-function components (structural + cooling) save volume and can reduce overall system mass. | Design and manufacturing complexity increases; repairs are more invasive and can raise replacement costs. |

| Hybrid systems (PCM + liquid): Combine short-term buffering with sustained heat removal to minimize peak temperatures and reduce pump sizing. | Higher BOM complexity and cost; careful thermal modelling required to avoid under- or over-design. |

Advantages of Active vs. Passive Systems

Active systems let you tightly control pack temperature under a wide range of ambient and load conditions, which directly reduces degradation rates and improves sustained power delivery; for example, maintaining cells within 15-35°C instead of allowing spikes above 45°C can materially extend cycle life and preserve capacity. You gain dynamic response (pump/fan speed, valve control) that lets you optimize for performance during fast charging or aggressive duty cycles and then scale back to save energy during cruise.

Passive systems, by contrast, give you reliability and simplicity: no pumps, valves or control software to fail, which benefits long-life stationary storage and low-power applications. If you prioritize minimal maintenance and lowest initial cost, you can size passive conduction paths and spacing to meet modest thermal loads, but you should accept that under peak loads you may see higher temperature gradients and reduced lifetime.

Cost-Benefit Analysis

You should quantify both upfront and lifecycle costs: active liquid systems typically add hundreds to a few thousand dollars to pack BOM for automotive-scale packs, plus recurring energy and maintenance costs, while passive approaches keep upfront costs low but can shorten useful life under heavy use. Operational energy draw for active cooling is usually modest-often in the range of 0.5-3% of vehicle energy during typical operation-but can increase under extreme cooling or during continuous high-power events.

To evaluate payback, model scenarios such as expected duty cycle, calendar life, replacement cost and energy efficiency penalties. For example, if active cooling adds $1,000 to pack cost but extends pack usable life by 25% in a high-duty application, that up-front expense can be justified; conversely, in low-power stationary backup where ambient control is available, the added cost may never pay back.

More detailed analysis should include sensitivity to variables like charging profile (fast charge frequency), ambient extremes and expected warranty period, because small changes in those inputs can flip the decision between passive and active solutions.

Environmental Impact Considerations

Your choice affects both operational emissions and end-of-life handling. Active systems increase manufacturing complexity and material use (pumps, heat exchangers, refrigerants), which raises embodied carbon relative to simple passive packs; however, by reducing capacity fade and extending service life you can lower lifecycle CO2e per kWh delivered. For refrigerant-based systems, selecting low-GWP fluids such as R1234yf (GWP ~4) versus older high-GWP options significantly reduces risk from leaks.

Materials like PCMs and dielectric immersion fluids bring recyclability and compatibility questions: paraffin-based PCMs are generally low-toxicity but add mass, while some advanced organic or salt-based PCMs can complicate recycling streams. You should weigh the environmental cost of added materials and potential contamination against the benefit of fewer battery replacements over the vehicle or system lifetime.

More specifically, assess end-of-life pathways and supplier disclosures for coolant chemistry and containment strategies; systems designed for easy fluid recovery and modular replacement tend to minimize environmental risk and regulatory burden.

Summing up

Taking this into account, you should approach thermal management in lithium‑ion batteries as an integrated set of choices: passive measures (cell spacing, TIMs, phase‑change materials) and active systems (air, liquid, immersion cooling) combine with smart pack architecture and BMS thermal control to maintain safe operating temperatures, limit thermal gradients, and prevent propagation. You must base selections on accurate thermal modelling, duty‑cycle expectations, and safety standards so your system balances energy density, weight, cost, and reliability.

You should validate designs with abuse and aging tests, implement real‑time monitoring and adaptive control algorithms, and plan for maintenance and end‑of‑life behaviors to sustain performance and safety over the battery’s lifecycle. By treating thermal strategy as a system‑level design parameter rather than an add‑on, you reduce risk, optimize performance, and extend the usable life of your battery packs.